Memoirs II

Memoirs II

Jula Isenburger as told to Sheila Low-Beer

About Berlin: I must say that Berlin in some sense was intellectually very amazing; the new openness, new pianists and violinists with technique breaking with tradition, the Eldorado cafe where the men were more beautiful and elegant than any woman, the famous Romanische cafe where Bertholdt Brecht presided as Sartre would later preside in a Paris cafe. There were so many things going on in the arts that were interesting.

[When Eric’s painting was attacked in the Nazi press, Wolfgang Gurlitt, owner of the gallery where Eric’s one man show was being held, advised him to go abroad. He and Jula went by train to Paris, as if on holiday.]

Escaping a threat, though never imagining the horror that was to come, we arrived in Paris, the legendary city we had always heard and read about. We almost forgot that we lost a way of life with a career for Eric and some possibilities for me. We had left all our worldly possessions with strangers, including some lovely cats. Somehow we thought we will return to it. We were not alone; so many of us of all ages, uprooted, bewildered, unable to believe that this was an end to all we knew and hoped for.

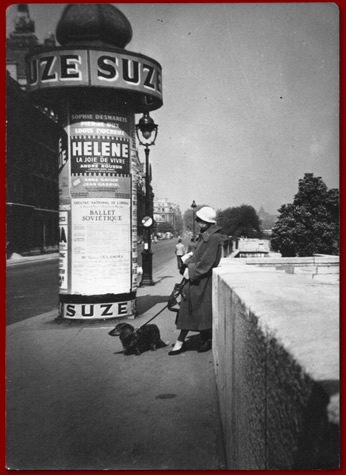

Meanwhile it was spring in Paris. The beauty of the city was intoxicating: it anesthetized one against fear of the future and it dissipated gloom. There was something exhilarating in the air, truly a joie de vivre. We were afloat without plans or ambitions, just a soaring feeling of life to be lived. We felt happy in the charm, gaity and urbanity of the life of the city, too young and inexperienced to be afraid of a vague future. It was wonderful to walk along the Seine with chestnut trees in bloom, all the bridges so splendid after the austere and uninspiring vistas of Berlin. The Louvre, the Jeu des Paumes, the Tuilleries, the magnificent views, and then the maze of ancient streets around Notre Dame, the intimacy of Left Bank life, the galleries in the Louis la Boetie–all seemed to be there for one to browse, to enjoy, to become part of.

All sorts of things were interesting in Paris at that time, such as Picasso exhibitions with Picasso’s changes from one year to another. Paris did not have much dancing but one great event was when we went to the Paris Opera and saw Ravel’s Bolero. The dancer was the very celebrated Ida Rubenstein and Ravel himself conducted–it was out of this world, fabulous! She was short, very thin and very straight, with the posture of a Spanish dancer.

Living in a room with a balcony in the heart of Montparnasse we embraced the Montparnasse ritual of sitting for hours over a cafe creme in the Cafe du Dome or Cafe de la Coupole. The model Kiki who had been a model for all the painters would go from table to table looking to me like an elderly gypsy–very run down but with enormous makeup and red hair, glad if invited for a drink or a cigarette; pathetic, but it was exciting to see her.

The small cafe tables were very near each other, inviting to neighborly chatting, conversation with new arrivals or hearing stories from old seasoned exiles about why they were there. They were lonely and liked to talk of their past lives. The almost provincial and quaint life of Berlin gave way to a panorama with a great range of human experiences.

Once we were invited by acquaintances to go have a glass of wine in a bordello in the street just behind the Cafe du Dome. The women were sitting half naked, reading the newspaper, discussing the latest murder sensation, paying no attention unless invited to work. It became a routine to go there and listen to discussions on politics, murder cases, etc. That was a very new window in my life. It was like going to a cafe. There was a great financial scandal in Paris–Stavitsky. How those women discussed it! And they had very wise opinions. In the same street was a little restaurant where we always ate cheap and bourgeois food with everybody having his napkin in a ring. Always the same: bifsteak, pommes frittes, yogurt.

Once we were invited by acquaintances to go have a glass of wine in a bordello in the street just behind the Cafe du Dome. The women were sitting half naked, reading the newspaper, discussing the latest murder sensation, paying no attention unless invited to work. It became a routine to go there and listen to discussions on politics, murder cases, etc. That was a very new window in my life. It was like going to a cafe. There was a great financial scandal in Paris–Stavitsky. How those women discussed it! And they had very wise opinions. In the same street was a little restaurant where we always ate cheap and bourgeois food with everybody having his napkin in a ring. Always the same: bifsteak, pommes frittes, yogurt.

Eric was working in the studio, producing many paintings. The special event that was very helpful was that the French artists invited the exiled painters to participate in the annual exhibition of the Salon d’Autonme. Eric fared very well in the press, described as the least teutonic, “almost French” in sensibility. It seemed to be an impetus to settle to work. A group of young painters who were well established on the Paris exhibition scene invited him to join them to work together on a boat on the Seine which they found inspiring. Eric joined them for a while but being reticent he left for the serenity of his own studio.

We rented a studio in the rue Cambon. This had a “suspende” with a bedroom and bathroom and in the entrance a small kitchen. The old routine of work came back, Eric painting and me rehearsing in the afternoons after renting an upright piano. I had at first a most accomplished pianist, Kosma, who after a relatively short time struck success and fame in the French movie industry, both playing and writing music. After Kosma went to the movies, every day for a few hours came a wonderful and sensitive pianist, Elsky, who was reduced to such minor work after fleeing Germany. He taught me much about French new music, Les Six, so that I used these to create dances.

At first I became a member and then soloist in a modern German group created by the German dancer and choreographer Weidmann. We were often engaged, sometimes to fill out an evening of entertainment, or as a special on festive occasions. When I found an agent I had recitals in the Pleyer Salle and after that in all sorts of cities in the French provinces.

When I left the Weidmann dance group for my own work, I was replaced as soloist by Lisa Fossangrive, who later became the most famous fashion model of that time when she arrived to USA. She modelled hats in Paris, but mostly danced as a pair with her husband Ferdinand Fossangrive. Years later he became a very fine photographer with exhibitions in New York and abroad.

One of the special friends we met in a cafe was Mrs. Morssing. She habitually sat alone and struck us as looking very sad and lonely but distinguished and resembling a pre-Garbo Scandinavian movie star. She was a sculptress who left her home in Sweden for a bright independent existence. Her husband had lost his fortune in the famous Swedish matches scandal that impoverished many Swedes. Her remittance from home was small and she confessed that she has to find work. She told us she could sew, and asked if I and friends would order dresses from her. As a sculptress, she said, she understands the body for which she creates. It turned out that she was a wonder, and could have been a great couturiere in another less turbulent and economically dour time.

After a while, when we started to take root in Paris and I found a dance agent, a Spaniard from the Basque who organized dance recitals for me, Mrs. Morssing executed all the costumes after Eric’s design. She became a member of the family, joining the secretary of the agent. Inspired by our needs I started to cook.

Buying in the enchanting street markets–bursting with fruits, vegetables and cheeses–became an inspiring routine. And so they arrived and the four of us settled every evening to dinner, with a bottle of vin ordinaire filled by the grocer, who encouraged me to learn to drink wine, not only for pleasure but for the santé. Slowly I overcame the sense that wine is sharp or inky. Mrs. Morssing would indulge heavily, becoming very chatty in her Scandinavian accent; San Esteban would stop brooding and tell stories of my agent who was really a famous cellist who had the agency to supplement his income. Always after dinner we would repair to the Cafe du Dome.

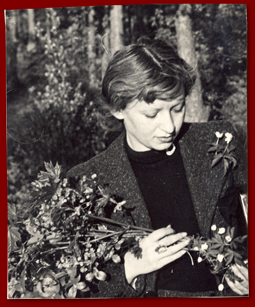

My decision to leave the Weidmann dance company and go on my own had been a heady decision. With the pianist Elsky I created twelve dances. He was steering me to the music of Ravel, Poulenc. . . .Eric designed the costumes and Mrs. Morssing went to work. Far from our usual haunts, she and I would go into stores who were known to sell remnants of fabrics from well known couturiers.

My decision to leave the Weidmann dance company and go on my own had been a heady decision. With the pianist Elsky I created twelve dances. He was steering me to the music of Ravel, Poulenc. . . .Eric designed the costumes and Mrs. Morssing went to work. Far from our usual haunts, she and I would go into stores who were known to sell remnants of fabrics from well known couturiers.

Often, sitting in the Cafe du Dome, we observed a smiling young woman equipped with a large camera rushing about photographing what one can describe as “types.” Her eagerness and enthusiasm were of a traveler who found a bounty. One day she stopped at our table. It seemed very complimentary for new arrivals to be suddenly a part of the tapestry of French bohemian life. In no time we discovered that we could communicate. She spoke German fluently; she was from Stockholm. Immediately we became great friends, meeting at the cafe and roaming in Paris, she with her large camera hanging from her neck. She told us about her very successful photographic studio in Stockholm, showing us pictures of the studio which was filled with photographs from Princess Ingrid to Max Ernst. She urged us to come to Sweden where she could arrange an exhibition for Eric and added that her brother and his wife would soon come to Paris. He was a publisher who published the first magazine of psychoanalysis and he would know how to proceed with the technicalities of this venture.

She departed and they arrived, followed by a younger brother who was extremely handsome and charming. We were told he was called “the Adonis” in Stockholm, with dark curly hair and melting brown eyes. His parents had emigrated from Russia to Sweden. He was irresisteble to the Swedish women and he carried the badge of several attemped suicides, none fatal. There was also a wife of a prominent Swedish citizen who followed him wherever he went, a non-scandal which he took lightly.

Suddenly embraced by such friends we were swept into unlikely adventures. The publisher introduced us to several German writers he was meeting. One of these was Hermann Kesten and his wife. We had read his books in Berlin and for his time he treated the erotica subject fully and explicitly. It was a revelation to meet him, a slight rather shy man though when in form very caustic. He was obviously in love with the Swedish publisher’s wife, who was a beauty, so his company was frequent.

One day the Adonis announced that he was in love with a young prostitute. He was seeing her in a neighborhood bordello. We already knew the bordello, initiated by the publisher that it was interesting and cozy to take there a beer or limonade. The women, mostly middleaged and half nude, were totally indifferent to the tourists who came and ordered a beer. They gossiped with each other, only interrupting when they were called to work. When we came there first they were absorbed in reading the Paris Soir, which then carried news of a famous murder case. They made remarks which were rude but with much common sense. To me, naive and half provincial, they were a total revelation.

Adonis wanted to give a party in the establishment to introduce his fiancee to the family. We were also invited and Mr. and Mrs. Kesten. The party was rather a failure. Though the girl was beautiful as well as delightful and well mannered, the others were politely subdued. Hermann Kesten was in agony. He was afraid even of the bottled water, that syphilis may lurk in it. It was clear he dealt more easily with erotica in his writing, just like a writer of jungle adventures who would not want to come near a snake.

Slowly we started to feel at home in Paris. Actually we felt at home from the arrival, but it took awhile to establish a pattern of life, Eric working and Mrs. Morssing sewing exclusively for me the costumes.

Summer was coming, and we took a few vacations to the north of Paris–to Dieppe with a painter friend from Paris who assured us that this is the loveliest place to be. The seashore wild, and high tides, and then the fishermen hauling their fish in the morning to an open fish market. To walk in the morning along this seashore and see the exhilarating colors of fish flapping on great tables was always a treat for us. The pension was for bourgeois middle class French families, with great food, the tables outside, not alone but just a green field with fruit orchard trees. We observed some curious French customs there, one mother pursuing her little boy with a glass of red wine, forcing him to drink it, saying “C’est bon pour le santé!”

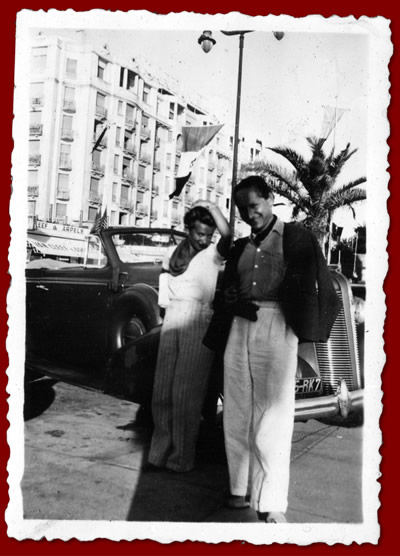

One summer we went to the Normandie, which was beautiful but often rainy. Then we decided at one point that Paris and its surroundings were too expensive for us and we decided to go to the Riviera. The Riviera in the thirties was almost deserted and the economy was very very low. The great and rich from Russia were now poor immigrants in Nice, just skimping on vegetables. You could recognize them in their hand embroidered linen dresses, once so fashionable but now sadly dated. They all seemed to live around rue de France–the part parallel to the end of the Promenade des Anglais going toward Cannes. There were very few English or other people though the Swedish king still played tennis there.

We felt totally in love being in Nice. It seemed to us to be the place to live, the vaster space of the blue sea with soft waves lapping at the white pebbles and the long curved and wide Promenade des Anglais, where you could sit for hours for a small fee on delicate chairs or wooden armchairs and read and drink, somnolent and at peace. The half moon shape of the Promenade, from the a bit lacklustre part to the middle of the curve facing the famous and luxurious hotels, like the Negresco, always having movie stars coming and going, proceeding to the middle of the town, passing a small park and ending at the old town.

We felt totally in love being in Nice. It seemed to us to be the place to live, the vaster space of the blue sea with soft waves lapping at the white pebbles and the long curved and wide Promenade des Anglais, where you could sit for hours for a small fee on delicate chairs or wooden armchairs and read and drink, somnolent and at peace. The half moon shape of the Promenade, from the a bit lacklustre part to the middle of the curve facing the famous and luxurious hotels, like the Negresco, always having movie stars coming and going, proceeding to the middle of the town, passing a small park and ending at the old town.

The carnation market was there in the old town. In those days Nice and the surroundings were shipping carnations everywhere. It was wonderful to see them in great piles along the old square where they were also packed for shipping in light loose bamboo. . . .There also was the splendid colorful market of fruits and vegetables grown around in the nearby hills–purple eggplant, brilliant greens, the juiciest reddest tomatoes, the sweetest figs, baskets of olives. There was also the tall narrow house where Matisse lived.

At first we stayed in a pension run by a German emigré woman in a short street between the Promenade des Anglais and the rue de France. We learned that in the same street lived the former publisher of the Berliner Tageblatt, the paper so influential in the politics of the time before Hitler. Just a few steps from the pension was a bathing establishment called Le Grand Bleu. There we spent entire days bronzing ourselves conscientiously and devouring the delicious pain beignons, a variation of salade nicoise in a baguette oozing with l’huile de Nice.

Nice and environs was the refuge of the literary and intellectual emigrés who fled Hitler–the great and famous and some less so, some who had means and some who had none. A group of them who lived in the city met late mornings in the Cafe de France. Nobody was interested in or wanted large commodious cafes. They had chosen a modest one with barely a view of the lovely sea, a small neighborhood cafe with uncomfortably light sidewalk tables on the corner of rue de France and the housewife-bustling avenue Gambetta where the tramway rattled noisily by. There were constant shoppers in this part of town, among them the Russians in their faded linen dresses. As the tram rattled by with great noise, the discomfort of the cafe and its lack of amenities and substance seemed to respond to the mood of loss and uncertainty.

We started to look for a permanent place and found it right across rue de France at the corner of Boulevard Grosso. There was a desolate garden with dusty palm trees and traces of a former larger and curved driveway. The garden was surrounded by a high metal fence. The imposing but rusty portals were permanently open onto the rue de France. In this dusty dilapidated place, to the right, behind the gate, was a two storey building with a sign: “Pension Marie Josie.” This was the place to which destiny would bring us later, where we lived for a time in semi-hiding waiting for the visa to USA.

Deeper in the garden was a long faded green building which had a sign: “Academie de la peinture.” We went to inquire. A long narrow empty corridor led along several studios, the first immensely large with many easels, podiums for models, casts of feet, hands and heads of gods and goddesses but empty of students. The second had on the door a card: “Madame de Stachiewicz, Directrice.”

A small round woman with a plain pleasant face, a chignon and using a cane, limping heavily, greeted us with a friendly smile. This second studio was large with two great windows, though smaller than the first one. It was a studio-living room, with Louis XVI armchairs, graceful tables with marble tops, etageres with silver dishes, opal vases, a huge sofa or rather an ottoman with innumerable embroidered pillows. There were Spanish shawls, one on Madame Stachiewicz, others on armchairs, and a soft carpet. The whole was opulent and antiquated.

She showed us the third studio in the row, which was for rent. We were enchanted. Our studio was much smaller than the second studio but quite comfortable to live and work in. It was charming with a single palm standing like a sentinel in the tall window. The furniture was a mixture of provencal chairs and salon-style armchairs. The bed in the corner near the window was a large white art deco piece. The whole was loveable and atmospheric.

There was no water. You had to fetch water with a large porcelain pitcher from the WC which was right out of the door in the corridor and wash in the basin. The whole washing arrangement was behind a Chinese silk screen–paravent–but there was the Mediterranean Sea just a few steps away. After not too long, Madame Stachiewicz offered us the use of the bathroom in her private apartment, which was below the studios. The apartment did not face the neglected garden but its windows were toward Boulevard Grosso. In those days Boulevard Grosso had a property of olive trees and wild anemones.

Madame Stachiewicz’ establishment consisted of her almost blind mother, who was tall and thin like a rope, and the Viennese cook, a refugee without papers hiding from the French police and very much given to overindulge in red wine. There were days he looked smart in a clean white jacket. On others there were shouting matches with Madame’s mother, who though blind never missed noticing the amount of carrots and onions or the diminishing wine. The war between the old lady and the wine-sipping cook broke out sometimes so that we could hear it above in the studios. Madame Stachiewicz limped down to the living quarters and after a while peace reigned again. She had a way of taming them.

The cook was a very good cook. When I was invited to make my entrecots in the kitchen he graciously advised me and invited me to taste his masterpieces–the goulashes, the pommes frites, the palachinken, the confits. Once Eric and I got carried away; we engaged him to cook a menu of his choice and invited friends. He rose to the occasion, totally sober, white jacket starched so that it creaked. He brought the hot plates from the kitchen into the studio, with maitre d’hotel manner. Such occasions broke his ennui.

One summer evening he escaped his sanctuary and was brought back heavily intoxicated by a policeman. There followed a long conversation in Madame’s studio and the policeman left without carrying him away for deportation, despite that the French police were always merciless with people who had no residency permit. We could only think that Madame Stachiewicz was a master of diplomacy.

We had many friends in Nice and we were very busy with our own life. But one day we felt something special was going on. Madame was constantly visited in her studio by her mother tapping along the corridor floor with her cane, or by the cook. A large black sea trunk made its appearance in the kitchen. Embroidered linen was carried around. Silver was polished and everything was waxed. Eventually we were informed that Monsieur and Madame Maurice Maeterlinck were making a visit to Madame for tea. They lived on the Riviera, lionized under the nimbus of admiration with which French people always surrounded great writers, not unlike the American people’s admiration for baseball heroes.

We were hanging out the window to see it all. A long nosed limousine came into the driveway. The Maeterlincks did not disappoint–in light elegant summer clothes and panama hat they mounted the creaky wooden steps to descend to the lower level. It was noblesse oblige, but it was also obvious that at some time Madame de Stachiewicz had a social standing on the Riviera.

Our landlady’s floors in the habitable studios had a fine pattern, intarsia-like, and were well kept. One day she prepared us that the special man who takes care of them would be coming. Nothing in the Stachiewicz entourage was as usual, but the appearance of this special man was creepy. I instantly named him the Golem (the creature invented by a rabbi in medieval Prague). I did not know of Frankenstein in those days. He was a very large man with sloping shoulders and long arms. He walked with bent knees and the face was a wooden mask. It was a dour face with no reflection of spoken word or sight. Maybe he was mute and deaf as there was no reaction to what was said or asked. He set to work wordlessly, cleaning, waxing, and then attached with string two huge brushes to his feet and moved slowly forward and backward, an eerie sight. In the end the floor looked like in Versailles.

When questioned, Madame de Stachiewicz just said he was a Russian refugee who didn’t understand or couldn’t speak French. A Russian refugee in the mid-thirties? We wondered, how did this prediluvian creature from the wild steppes of Russia land on the Cote d’Azur? Of course he was there from the first world war, when he had been a lowly servant of the fabulous Russians who would descend with entire households in the European fashionable places. There were stories told and written of how the Russian aristocracy, with Byzantine splendor, would arrive with their nannies, cooks, coachmen and armies of servants for doing daily chores. All those years since, like a stray dog he survived on human kindness.

She did not say he lived there, but one day, alone in the kitchen, waiting for a dish to get ready, I saw a low door, never observed before, that led to a very large dark basement. Descending the rough wooden steps I slowly got used to the darkness. The only light came from a few narrow strips of window that just were showing the pebbles of the garden. There were many black sea trunks. I started to imagine some splendid old wardrobes, silver (heavy silver), and the embroidered linens that once were exhibited when the Maeterlincks came to tea.

Turning back to the steps I became aware of a tiny birdcage next to one slit of light in the corner behind the steps. There was a small bird in it, and there too I saw a curtain, separating the corner from the rest of the basement. I peeked behind and saw a bed made of plain wooden planks, a table with a kerosene cooker and the two huge brushes for polishing the floor. I fled back upstairs. After that for quite a while I didn’t go to the kitchen but we ate our dinners in a small pleasant prix fixe in the rue de France.