Moments of Decision

Moments of Decision

Sabine Kammerl

How many thousands and thousands of decisions does a person have to take during his or her life?

How many decisions are made when art is created?

Do decisive moments in life influence those in art and those in art influence those in life?

Eric Isenburger’s decision to become a painter is a decision to live, to observe and to work in a certain way. The decision to lead his life with Jula and her decision to lead hers with him significantly determine the personal and artistic development of them both.

In 1928, only a few months after Eric and Jula fist meet, they marry, leave Frankfurt am Main and move to Vienna.

Setting out on the chosen path of life and the beginning of a long chain of locations. Each place they are to choose will leave behind a distinctive mark in the lives and work of them both.

In Vienna, Eric enables the seventeen-year-old Jula to realise her dream of dancing. First in Hellerau, and then with the dancing teacher Gertrud Kraus, Jula Isenburger explores her ability of expressiveness as a dancer. Jula organises life together and is Eric’s most important bridge to the outside world, which he approaches above all through his painting. He paints portraits of Jula’s teacher Gertrud Kraus, friends, dancers, actors and actresses, writers and choreographers.

The people portrayed in his paintings appear distressed and melancholic, yet determined to make their work important for the world around them.

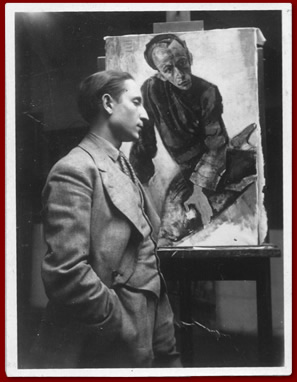

In one of the photographs taken by a friend, the Swiss photographer Imboden, Eric Isenburger is standing in front of the portrait of the choreographer Fritz Klingenberg, wearing an impeccable, elegant suit and looking serious and pensive. The way the artist sees himself as a member of middle-class society is undiminished. The painting on the easel, on the other hand, conveys the calling in question of conventions and the search for new forms of expression.

In one of the photographs taken by a friend, the Swiss photographer Imboden, Eric Isenburger is standing in front of the portrait of the choreographer Fritz Klingenberg, wearing an impeccable, elegant suit and looking serious and pensive. The way the artist sees himself as a member of middle-class society is undiminished. The painting on the easel, on the other hand, conveys the calling in question of conventions and the search for new forms of expression.

Eric Isenburger’s adventures take place in his head and on the canvas.s. He does not present his artistic genius outwardly. His paintings depict his understanding of the inner conflicts and the strengths of his contemporaries and the age he lives in.

Both Eric and Jula, each in his and her own way, create pictures of a feeling for life that is determined by curiosity and the joy of experimenting – through drawing and colour on the surface of paper and canvas, through the movement of the body in space.

In 1931 they decide to move to Berlin.

Eric paints portraits of newly-won friends. Motives of black dancers and figures painted from imagination without model appear on the scene.

His painting technique changes. The palette remains dark, yet earthy colours mixed with sand shine through black and brown tones. Now and then a contrasting field of colour lights up. He incises contours of faces and figures into the intricate priming.

The paintings appear iridescent between the incised lines and the spatial layers of paint. The fascination of foreign cultures and the longing for their imagined originality and directness shine out in them. The studio in Berlin, designed by an architect friend of theirs, is to become the new central point of Eric and Jula’s work and lives. A photograph taken from the gallery of the distinctive, bright room shows Jula dancing. She is now a member of the Mary Wigman School in Berlin. In summer 1932, she has already become a solist with the Wallmann-troupe performing at the Salzburg Festival. Eric Isenburger is under contract to the gallery owner Wolfgang Gurlitt. In 1933 public acclaim seems near. Although Eric Isenburger’s one-man show of his new paintings receives enthusiastic reviews, he and Jula are urgently warned by Wolfgang Gurlitt about articles in the right-wing press that describe Eric Isenburger’s work as degenerated. He advises the couple to go to France for a while until the situation cools down.

This further escalation of the political situation is a shock for Eric and Jula. Concentrating on the development of their artistic work lies at the centre of their lives. And they are so busy building up their lives as artists in Berlin that they have until now regarded the political complications as momentary, unimportant and uninteresting occurrences. They leave the recently completed studio in Berlin with little luggage. It becomes clear that their departure from Berlin is to be a final one.

On leaving Germany Eric Isenburger abruptly gives up the dark palette and the direct, dynamic painting technique he used. He has left not only paint and canvases behind in Berlin, but also a feeling for life. Drawings and colour sketches in pastel shades are made on transparent and oil paper. A radical break has been forced upon him, and he reacts to it with a radical change in his work.

He reacts to the harshness of the political atmosphere by searching for the fragile, melancholic beauty in people, things and landscapes. The tones of the paintings become lighter, the application of paint thinner and more transparent. The lines that Eric Isenburger used to draw so very decisively with a palette knife into the layers of paint have now becomes fine contours and patterns. A smile can be seen on the faces of those portrayed. People, landscapes and objects give the impression of being shadowy silhouettes, as if covered by haze.

In Paris, Jula, under the name of Jula Geris, and accompanied by the pianist Elskin, puts together a successful dance Programme of works by Bartok, Debussy, Gershwin and Satie. Madame Morssing, a Swedish sculptress, models Jula’s costumes after designs by Eric Isenburger. Anna Riwkin, a Swedish photographer takes impressive photographs of Jula in her stage costumes and takes portraits of the Isenburgers.

In 1936, Eric Isenburger accepts an invitation to go to Sweden. In spite of Eric’s success in Stockholm, he and Jula feel themselves drawn back to France, which has become a new artistic home for both of them.

In 1937, they move to the south of France, like many other emigrants. Germany and the Nazis seem a long way away.

Following the occupation of Paris in 1940, the German emigrants in unoccupied southern France are, absurdly enough, suspected of being sympathisers of the Nazis they had fled from. Hundreds of men are interned in Les Milles, a onetime brick factory covered with red dust. Eric Isenburger draws dozens of portraits of his fellow-prisoners and the French guards.

Drawing in this unreal place and this absurd predicament gives the impression of his being strangely peaceful and contemplative. It is a means of searching for the nature of man and provides a way of dealing with the environment that is radically different from the one prevailing in the struggle for power in Europe.

When a fortunate opportunity arises to leave France and Europe with Jula, possibly a chance that would not come again his way again, Eric Isenburger seizes it without hesitation.

The ship to New York is to put to sea from Lisbon, yet getting to Lisbon is a nerve-racking venture as the Isenburgers are in posession of entry permits for the United States but not for fascist Spain.

When Eric and Jula Isenburger finally arrive in Lisbon, the ship that they were to show their tickets for as proof of their intention to emigrate has already set sail. For weeks they have to wait for the next opportunity to sail and they request money for the new tickets from distant relatives.

Destitute, Eric and Jula Isenburger arrive in New York in 1941.

Within a year of their arrival, Eric Isenburger’s paintings are exhibited in the Knoedler Gallery, New York and buyers and collectors are soon to be found.

Jula Isenburger abandons a resumption of her career as a dancer. The couple’s entire energy is concentrated on the success of Eric Isenburger’s painting.

Jula is Eric’s model and most important interlocutor. The pictures he paints of her illustrate the coupe’s very special closeness and attachment.

After the war, Eric and Jula Isenburger travel extensively. Again and again they feel drawn to Europe, but Europe is only nostalgia, a lost future. A holiday place whose beauty seems unreal and fragile.

In his paintings, Eric Isenburger seeks the constantly fleeting.

While painting, he asks himself what beauty can be. He looks for possible answers in everything around him. And he finds them again and again in Jula, in the landscapes and towns they visit together, in flowers, interiors and still life.

Grey is described by Eric Isenburger as the most important colour in painting. Grey is often put under or just next to other colour tones, making them glow gently. Yet pure colours shine too, and provide a strong contrast to the delicacy around them.

The different areas are composed of patches of paint through which grey priming shimmers. Brush strokes, lines and shapes stretch across these areas of colours and give them structure.

Painting is life for me (. . .); when I sleep, I carry on painting in my dreams, he says in 1962 while visiting Munich on his way to Venice.

Yet the artistic means never break away from the moments of beauty that Eric Isenburger captures in his paintings.

. . .can I convey the magic of Venice or the eyes of my wife in an abstract way? Never! . . .he ads during the interview with the Munich reporter.

On Eric Isenburger’s decision to devote his life to painting began his unwavering search for the quiet strength of beauty and the fleeting moments of its appearance.

Individually and jointly, the moments Eric Isenburger captured in his paintings tell their own, unique and happy story of their times.

~ Sabine Kammerl, 1999

from “Eric Isenburger 1902-1994 Ausgewählte Werke Städtische Galerie im Rathausfletz Neuburg an der Donau 2. Mai – 13.Juni 1999” (Neuburg 1999), pp 17-18